Chapter 11 of In Light of Eternity, by Randy Alcorn

The story of Randy’s friendship with Jerry Hardin

When I ponder the adventure that awaits us in Heaven, the joys and the fellowship, my thoughts drift to my friend Jerry.

In 1965, as sixth graders, we became best friends. We spent our “wonder years” together. Side by side we patrolled our turf, a few rural Oregon miles of rolling hills, open fields, and sporadic houses. Today, more than thirty years later, I ride my bike over the same ground. Every corner, every driveway, every house and field triggers memories of a time in my life inseparable from Jerry.

Out in those fields, hidden from the rest of the world, he and I engaged enemy soldiers, hunted wild animals, dug up treasures, and encountered aliens. Sometimes I still walk around our little grade school where we spent so much time shooting baskets, throwing footballs, playing catch, and riding our bikes. Then on Friday nights we got civilized, spiffied up and went to junior high parties together, reeking of Jade East and Brut, intended to make us irresistible to the girls. (They never fell under our spell.)

Every summer we’d go together to the County Fair, proving our emerging manhood by proudly enduring all the scariest rides. We’d eat corn dogs and cotton candy till we were sick. We threw dimes and won goldfish and carnival glass and stuffed animals, first for our moms, then our girlfriends. One summer, imagining we were cool (trust me, it required a lot of imagination), we wore those stupid Nehru shirts with the high collars, the ones that were in fashion maybe two weeks.

Most Saturdays we went to the Hood Theater, watching matinees now relegated to the oldies section in video stores. Some of the titles still make me think of the guy who shared those giant tubs of popcorn with me as we watched and snickered and exchanged inane comments. I’ve taken my own teenagers to that same theater, virtually unchanged. The same Ju-ju-bees and Good-and-Plenty Jerry and I dropped are still stuck to the floor right where we left them. Certain seats in the balcony still trigger the time warp that takes me back to those years so closely linked to Jerry.

Favorite places. Unforgettable adventures. On display in my mind is an endless collage of games, journeys, field trips, concerts, awards assemblies, and countless little vignettes containing Jerry. Like the eighth grade musical where Jerry had the lead and I shared the final scene with him. At the climactic moment he ran to the big heavy hanging microphone where he was to burst into song. But he’d miscalculated and couldn’t stop in time. He smashed his head on the mike, causing it to swing back and forth like Tarzan’s grape vine. All the horrified parents and family in the audience didn’t deter me from laughing nonstop for twenty minutes. Memorable mishaps like that, accumulated over the years of childhood and adolescence, are the bricks and mortar of a unique sort of friendship, the kind those who first meet as adults can’t know. Best friends aren’t always your oldest ones, but there can never be any friends like early ones.

Favorite places. Unforgettable adventures. On display in my mind is an endless collage of games, journeys, field trips, concerts, awards assemblies, and countless little vignettes containing Jerry. Like the eighth grade musical where Jerry had the lead and I shared the final scene with him. At the climactic moment he ran to the big heavy hanging microphone where he was to burst into song. But he’d miscalculated and couldn’t stop in time. He smashed his head on the mike, causing it to swing back and forth like Tarzan’s grape vine. All the horrified parents and family in the audience didn’t deter me from laughing nonstop for twenty minutes. Memorable mishaps like that, accumulated over the years of childhood and adolescence, are the bricks and mortar of a unique sort of friendship, the kind those who first meet as adults can’t know. Best friends aren’t always your oldest ones, but there can never be any friends like early ones.

I remember Jerry and I picking (and throwing) berries at dawn on summer mornings, then spending our afternoons swimming and listening to the Beach Boys and Simon and Garfunkel, switching channels on our squawky eight-transistor radios and reading comic books starring Superman and Batman, who epitomized male strength and heroism. We’d talk about cute girls and adventures and exploits, and what we’d do when we grew up. We’d haul out our sleeping bags and camp out under the stars in my back yard, with Champ, my golden retriever. We’d look through my telescope at Jupiter’s moons and Saturn’s rings and the great galaxy of Andromeda and wonder what life was all about. (In those days we didn’t know.)

Our eighth grade year, Jerry made wide receiver and I quarterback. On weekends, we’d walk from his house to mine, throwing the football back and forth, dreaming of great victories. (Few of these ever materialized, but shared dreams create their own bond.) After working up a sweat, we’d make the trek to Miller’s Store and share a bottle of Byerly’s orange soda.

We excitedly watched them build a brand new high school, located right between our houses. We’d be the first four-year graduating class, experiencing and defining the school from its inception. In that freshman year, Jerry and I met the girls we’d later marry, his Carol and my Nanci.

Something else happened in high school, something which would forever shape and transform our friendship. Jerry and I became Christians. Now we spoke of new dreams, loftier ones, informed by new realities. Our deep friendship became permanent not just in sentiment, but in fact. Now we were brothers in an eternal sense.

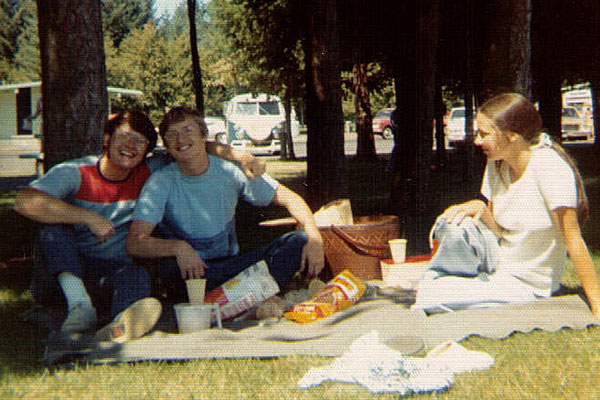

Soon after getting married, Jerry and I and my wife Nanci and his wife Carol drove together in a Volkswagen bug on a two-week vacation in California. In the following years we played tennis, talked theology, shared our hopes and struggles. As we raised our children and got deeply involved in our churches and work, the demands of life dictated we spend less time together, but every time we met, often on the tennis court, we picked up exactly where we left off. He was always the same man—steady, consistent, quietly faithful. As dependable as Big Ben and Oregon rain.

Soon after getting married, Jerry and I and my wife Nanci and his wife Carol drove together in a Volkswagen bug on a two-week vacation in California. In the following years we played tennis, talked theology, shared our hopes and struggles. As we raised our children and got deeply involved in our churches and work, the demands of life dictated we spend less time together, but every time we met, often on the tennis court, we picked up exactly where we left off. He was always the same man—steady, consistent, quietly faithful. As dependable as Big Ben and Oregon rain.

In 1992 I served on the planning committee for our twenty-year high school reunion. I asked if Jerry could speak to our class the first night of the reunion. There was a special reason. At age thirty-eight, Jerry was dying of cancer.

Chemotherapy had left him bald. As I blearily watched him speak that night, I prayed that his words of faith and hope would make a deep impact on our old classmates. They did.

After Jerry was diagnosed as terminal, he and I talked about suffering, healing, and heaven. I picked out lots of books for him, and he read them all. We talked about God’s grace in giving him time to prepare for what awaits every one of us. We prayed together for his wife and children. He’d lived well, and didn’t have to make many changes to be ready to die and meet his Creator. I told him that.

Only a month before he died we played tennis together the last time. When I lost a point, he’d accuse me of going easy on him. When I won, he’d accuse me of taking advantage of a man dying of cancer. We laughed and kidded each other as only the best of friends can.

God forged our lives together in the same foundry, beginning years before I knew there was a God. That kind of history links two souls. In a strange combination of pain and pleasure, in our last times together we sensed the earthly phase of our friendship drawing to completion. In our final coherent conversation, after I’d read to him a number of Bible passages, I said to Jerry, “We were made for another world, not this one.” He smiled and said with a weak voice, full of conviction, “Amen.”

Jerry got steadily worse. His family brought him home from the hospital, as he desired. On a Thursday morning I headed to the airport, for a speaking engagement in Philadelphia. I decided to leave home an hour early and drop by to see Jerry.

Jerry got steadily worse. His family brought him home from the hospital, as he desired. On a Thursday morning I headed to the airport, for a speaking engagement in Philadelphia. I decided to leave home an hour early and drop by to see Jerry.

While Nanci sat with Carol in another room, I went to Jerry alone. I hunkered up close to him and read him the last two chapters of the Bible, the same passage I’d read to my mother many times when she was dying. (It was eleven years to the day since she died.) As I read Revelation 21:4, “God will wipe every tear from their eyes,” I looked up and saw tears in one of Jerry’s eyes. I wiped them away.

I continued to read, through my own tears, right up till Revelation 22:17. “The Spirit and the bride say, Come!’ And let him who hears say, Come!’ Whoever is thirsty, let him come; and whoever wishes let him take the free gift of the water of life.”

Between the time I started reading that verse and the time I finished, something powerful and wonderful happened. Jerry went home.

My friend left his temporary residence, his interim home away from Home. One moment he was laboriously breathing the stale air of earth, the next he was effortlessly inhaling the fresh air of heaven.

I had the privilege of being there the moment he walked through that door between two worlds. I had the privilege of saying the last words he heard in this world. The fact that they were God’s words, and a specific invitation to come to heaven, heightened my sense of honor in being with Jerry in life’s most defining moment, the moment of death.

I was there when Jerry signed his life’s portrait, when the paint dried, the picture was hung and the artist went on to bigger and better things. I could almost hear a voice in the world next door, someone saying to my friend, “Well done.” (Those who’ve read my novel Deadline will notice I patterned Finney’s death after Jerry’s.)

I’d been there with Jerry at our grade school and high school graduations, and I was there with him at his most important graduation, from this life to the next. I’d stood by him as best man at his wedding, as he had at mine. My final tangible act of friendship in this life was to conduct his memorial service, a tear-filled, laughter-filled Christ-centered celebration of his life.

Looking at Jerry’s uninhabited body as I sat next to his bed reminded me of what both of us knew and had openly discussed. Death is the dissolving of union between spirit and body. The body dies but the person lives on. Death is not a wall, it’s a tunnel. It’s not an end, it’s a transition.

When Jerry died, the room took on a profound sense of vacancy. His body was a temple in which his spirit and God’s had dwelt. The moment he died, the temple lay deserted. “Ichabod”—the glory had departed. Jerry’s wasted body was not what was left of him. It was simply what he left. Jerry didn’t end. He just relocated. He didn’t cease to exist. He just got up and walked out, and went where I couldn’t see him from here.

When I think of friendships without Christ, it saddens me to realize they’re like old clocks, winding down with each tick, destined to ultimately stop, the mainspring forever broken, never to be wound up again. My relationship with Jerry wasn’t like that. His death wasn’t an end to our friendship. It was only an interruption.

Our time here was the preliminaries, not the main event, the tune-up, not the concert. The friendship that began on the old earth will resume and thrive and grow in the present heaven, where Jerry is now, and then on the new earth, the world for which we were made, a world of wonders beyond our wildest dreams.

I miss you, Jer. Pick some favorite places we can hang out when I get there, okay? And then we’ll have the New Earth to look forward to. Maybe will go back to the new versions of the old places we used to hang out.

The real adventures are still to come, aren’t they?

I long for the great reunion, old friend.