Note from Randy Alcorn, March 2017

Most of the long article that follows was written in 2008, when The Shack had sold less than a half million copies. It has now sold over twenty million.

I’ve had no desire to step into controversy in a public discussion of The Shack. However, after years of silence, time has demonstrated that many people are indeed basing their theology on The Shack.

The author has since published a devotional drawn from The Shack. He also wrote the foreword to C. Baxter Kruger’s book The Shack Revisited: There Is More Going on Here Than You Ever Dared to Dream, which in Young’s words, is meant to help readers “understand better the perspectives and theology that frame The Shack.” Additionally, a major motion picture based on the book has been released.

Shortly after the movie came out, Paul Young’s book Lies We Believe About God was published. I’ve finished reading it, and for sure, this book changes the debate about The Shack by showing the author’s actual theology.

Ironically, many of the concerns that I and many others expressed about The Shack (and in response, were told “it’s just fiction” and “this isn’t theology” and “that’s not what he means”) have proven to be valid all along.

I wanted to believe the best, and not be quick to misunderstand or accuse. However, this new book shows in the author’s own words how far he has departed from some basic and central evangelical doctrines. As I read it, I saw truth intermixed with unbiblical error. But as is often the case with false doctrine, the truth serves to make the error appear more credible.

I am disappointed and concerned that the countless people influenced by The Shack and many of its more implicit errors will be taken by Lies We Believe About God into increasingly significant explicit errors.

In reading Lies We Believe about God, at times I marveled at all the precious truths the author is calling outright falsehood. For instance, he claims all these are lies:

- God is good. I am not.

- God is in control.

- God does not submit.

- God wants to use me.

- You need to get saved.

- Hell is separation from God.

- Not everyone is a child of God.

- Sin separates us from God.

- The Cross was God’s idea.

These are not lies. They are truths, and there is plenty of biblical support for each of them. Of course, not everything everyone says related to these truths is accurate (but that’s always true). To say these are all “lies” is unbiblical, irresponsible, and misleading.

While I could elaborate with a number of Scriptures for each of these, take just the last one, said to be a lie: the Cross was God’s idea. Acts 4:27-28 says, “Indeed Herod and Pontius Pilate met together with the Gentiles and the people of Israel in this city to conspire against your holy servant Jesus, whom you anointed. They did what your power and will had decided beforehand should happen.”

We could add the words of Isaiah 53, that Jesus was “punished by God, stricken by him, and afflicted. But he was pierced for our transgressions, he was crushed for our iniquities; the punishment that brought us peace was on him, and by his wounds we are healed. We all, like sheep, have gone astray, each of us has turned to our own way; and the LORD has laid on him the iniquity of us all…for the transgression of my people he was punished….though he had done no violence, nor was any deceit in his mouth. Yet it was the LORD’s will to crush him and cause him to suffer.”

Here is a book supposedly identifying lies we believe about God while dismantling biblical truths at the heart of the Gospel message. It attempts to replace these truths with...you guessed it...ACTUAL untruths, lies about God!

If it seems unfair for someone to say the author is speaking lies, consider that his entire book is dedicated to the idea that evangelical pastors and Christ-followers who have been teaching these biblical doctrines for hundreds or thousands of years are liars.

Paul Young admits at last (I had two previous three-hour conversations with him in which he wouldn't quite fully admit it yet) he is a universalist: “Are you suggesting that everyone is saved? That you believe in universal salvation? That is exactly what I am saying!” (p. 118). That makes it official: no more arguments about whether The Shack teaches universalism.

The truth is, we desperately need to be saved by Jesus, that is, to embrace what he has provided on our behalf: “We implore you on behalf of Christ, be reconciled to God” (2 Corinthians 5:20). We need to be saved from our sins, to be rescued, delivered, reconciled, and born again, so we can enter into God’s goodness and the righteousness of Jesus.

I recommend this summary of some of the unbiblical content in Lies We Believe About God, well expressed by Tim Challies.

While Paul Young remains a likable person, this doesn’t change the danger of revising God’s truth and telling people nice-sounding things on God’s behalf, when some of those explicitly contradict what He tells us in His Word.

You may notice that in the following article, I tried my best to be fair to The Shack and its author. I expressed my concerns to him with the genuine hope that it might influence his thinking and that perhaps he would even change some of what he’s written that I believe is unbiblical. The passing of time and his writing new things that I think violate God’s Word makes this increasingly unlikely. I decided not to change what follows (with the exception of minor things such as updating book sales), but the more recent developments have not given me lesser but greater reasons for concern.

My Preface to the Reflections, Added in 2012

For a variety of reasons, including my hope for further interaction with the author and my desire to not be part of another controversy (I’ve been in my share), I originally decided not to publish this or post it online. When people asked me about it, I told them they could request this unpublished paper.

It now seems appropriate to finally post an updated version of what I wrote years ago, since I still receive so many questions about the book, and now still more because of the movie.

I’m also posting it because of the ongoing trend of unbiblical theology surfacing in supposedly Christian books (see my comments on Mary Neal’s To Heaven and Back, blog 1 and blog 2). This is a problem that didn’t start or end with The Shack but it’s now something I think I should address.

Reflections on The Shack

Randy Alcorn

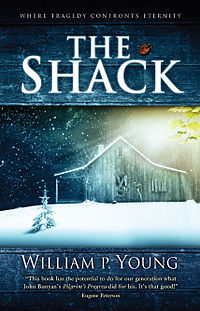

A couple of months after The Shack was self-published in May 2007, with most copies being distributed from his car, the author gave me a copy and asked me to read it. It hadn’t sold many copies, well less than a thousand I’m sure, and I knew almost nothing about it. Six weeks later I read it from cover to cover.

A couple of months after The Shack was self-published in May 2007, with most copies being distributed from his car, the author gave me a copy and asked me to read it. It hadn’t sold many copies, well less than a thousand I’m sure, and I knew almost nothing about it. Six weeks later I read it from cover to cover.

In the fall of 2007 I started getting calls about it. A couple of years ago I received an inquiry from a pastor in Russia. I continue to receive inquiries to this day, asking me if I’ve read The Shack, and what I think of it.

By February 2008, when I met with the author to discuss the book, he told me it had sold over 200,000 copies, with a marketing budget of about $200. But three months later, a year after its release, it had sold over 700,000 copies. As of February 2017, according to Publishers Weekly, it has sold over 22 million copies across all formats worldwide! It is now one of the best-selling Christian books in history and has been translated into many other languages.

If you aren’t familiar with The Shack, you can learn more and check out the reviews on Amazon.com. You would be hard pressed to find a higher percentage of 5-star reviews for any other book. The level of devotion readers have for The Shack is stunning. People buy it by the case and pass it out to their friends. It’s word-of-mouth at the highest level. There’s been some backlash due to theological problems in the book, but the backlash has been minimal compared to the acclaim.

There Is Good in The Shack

First, let me say that I think there’s good in The Shack. It has helped many people see the warmth within the triune God, and God’s warmth toward them as well. For that I am grateful.

John Owen portrayed the personal nature of the triune God hundreds of years ago, and John Piper does it in The Pleasures of God. Those studies are biblically oriented, and I could wish that people would draw more from them and from Scripture than from a novel. But novels capture people’s imagination in ways no other literary form can. Having written several novels, I certainly would not dismiss The Shack on the basis that it’s “just a novel!” Novels can be a powerful vehicle of not only telling a story, but also conveying concepts, both right and wrong ones.

The Shack raises the problem of evil and offers God’s love and hope to those who’ve been overwhelmed by tragedies they can’t reconcile with God’s sovereignty and goodness. I appreciate the fact that Paul Young doesn’t resort to openness theology, to argue that God doesn’t know about the evils that are going to happen and therefore can’t prevent them. He sees God as all-powerful, all-knowing, and all-good. And he certainly gets in touch with human need, weakness, and grief. The most memorable phrase from the book, for me, is “The Great Sadness,” an expression that connects to many people’s deepest hurts, regrets, and longings.

More than any other book I recall, I find myself in the curious position of attempting to balance the reactions of each person who asks about it. When people say they can’t stand it, I point out the good stuff and say people are seeing God’s warmth and grace and forgiveness in fresh ways. When the response to the book is unqualified praise, I caution readers about the theological weaknesses.

Eugene Peterson (a man I respect) says that The Shack may be The Pilgrim’s Progress of our generation. I think that’s an overstatement. I wonder if he’s read it with careful attention to some of the theological details.

In my experience, most Christians who have read the book adore it. There are people I respect greatly who love this book, without qualification, and consider it a great gift of God to thirsty people. There are others I respect as much who are deeply concerned about the book’s messages, both overt and subtle, and their impact on people. In a sense, both might be right, but both need to understand the other point of view and that many books that are good for some people are not good for others.

I believe that those who are well grounded in the Word won’t be harmed by the weaknesses and deficiencies of the book. Unfortunately, increasingly few people these days are well grounded in the Word.

I think this book would have better served the church thirty years ago when there was so much more legalism, and too little talk of God’s grace and forgiveness. Ironically, though there’s still some legalism, there is also significantly less knowledge of Scripture and spiritual discernment and concern for orthodoxy. That means some people, perhaps many, will fail to recognize and filter out the book’s theological errors, and therefore be vulnerable to embracing them, even if unconsciously.

The Danger of Putting Words in God’s Mouth

Most of the dialogue in the book comes out of the mouths of four characters. One is Mack, who has faced a horrible tragedy with his daughter. The other three primary characters happen to be, in human forms, the three members of the triune God. (This novel gets points for boldness!)

In conventional novels, when characters, Christian or not, say things, we can always explain, “That doesn’t mean he’s right.” While I’ve said to some people, “Remember this is fiction, so don’t try to hold it up to the standards of nonfiction,” it rings a little hollow, because the obvious point of The Shack is to make numerous theological statements.

The story is largely the wrapper; the “truths” are what’s inside it. It’s hard to fall back on “Yeah, but it was just one of the characters saying that” when the character happens to be God. You can’t really say “he was having a bad day,” or “he wasn’t familiar with that Scripture.”

When I pressed a few theological points with Paul Young, he said he wasn’t trying to write theology; he was writing a novel. But as a novelist, I know that it’s not only possible to communicate theology through a novel, it is virtually inevitable. Certainly you cannot have characters representing God say things without everything they say being a theological statement! The only question is whether it will be good theology or bad theology. For a couple of years I heard people repeatedly say, “Don’t judge The Shack like you would a theology book—it’s just a story.” Well, not only does that insult stories, as if they don’t contain truth, but it also radically underestimates the theological content of The Shack.

When The Shack was picked up for distribution by a Christian publisher and released at a booksellers’ convention I attended, a huge promotional sign visible a hundred feet away asked, “What is God like?” The answer—so they said—was found in The Shack. The book wasn’t about theology? Well, theology is the study of God. And there is no more direct and basic theological question than the one the publisher claims The Shack seeks to answer: “What is God like?” I pulled out my camera, took a photo of the sign, and occasionally showed it to people in future conversations when they said, “It’s not theology; it’s just a story.”

Granted, I tire of people telling me they disagree with what various characters say in my novels. Of course they do, and so do I! I put unbelievers and misguided believers in my books who say things that aren’t true, or are only half true. These should normally be easily identified by the reader. But The Shack is very different. When it puts words in God's mouth, words other than God's as revealed in Scripture, the author subjects himself to a higher standard. Mack can and does say all kinds of wrong things and the author shouldn't be held accountable for them, because Mack is only a flawed human character. But when a member of the triune God says something that is contradicted by Scripture or known fact, it’s another matter.

Some criticize the book for what it leaves out, or fails to emphasize. This is not always valid. A book—particularly a novel—doesn’t have to be completely balanced. Young’s primary subject is God’s grace, not God’s holiness. So holiness is given little attention, if any. That’s okay if—but only if—the reader already has that concept clearly in mind. But if the reader doesn’t have a concept of God’s holiness, then I think the exclusion tends to propagate a serious error, a wrong view of God. Scripture speaks of the “kindness and severity of God,” and that it’s a fearful thing for the sinner to fall into the hands of the living God. If the book portrays the triune God page after page but never shows that side of Him, I think it’s regrettable.

Things That Concern Me

“You will learn to hear my thoughts in yours” (195), says Sarayu, the Holy Spirit. “You might see me in a piece of art, or music, or silence, or through people, or in Creation, or in your joy and sorrow. My ability to communicate is limitless, living and transforming, and it will always be tuned to Papa’s goodness and love. And you will hear and see me in the Bible in fresh ways. Just don’t look for rules and principles; look for relationship—a way of coming to be with us” (198).

At times I felt the book didn’t teach the sufficiency of Scripture as God’s primary revelation. Yes, I agree that God speaks through flowers and animals and people and art. But I wish the Bible was, even in the above quote from the book, not simply put alongside them, but clearly put on a higher level. I wish the Holy Spirit (Sarayu) showed more enthusiasm for the Book that is Holy Spirit-inspired.

I wish The Shack had an Acts 17:11 tone: “Now the Bereans were of more noble character than the Thessalonians, for they received the message with great eagerness and examined the Scriptures every day to see if what Paul said was true.”

With the book’s repeated message that the Bible has been twisted by churches and pastors and seminaries (and yes, sometimes it has), I wonder whether readers will walk away from The Shack with a greater love for Scripture and more of a desire to study it, and more of a desire to get involved in their churches and submit to their leaders, as Hebrews 13 commands us to. Sadly, I’m afraid some readers will feel justified in further distancing themselves from both the Scriptures and the church. And some may read meanings into Scripture that the biblical text itself contradicts.

While any book that portrays the trinity in physical form is going to be subject to criticism, given the premise, I thought it was fine that the Holy Spirit was portrayed as female. I was somewhat concerned that “Papa” was also a female; but the reason for this is later explained in the text, in terms of Mack not being able to accept God as Father because of his bad relationship with his human father. Later Papa is depicted as a male.

In real life, though God certainly reveals Himself through any number of godly women, I don’t see biblical examples of God the Father portraying Himself as female to people simply because their fathers are absent or aren’t good role models. Because I had a very poor relationship with my earthly father when I came to Christ (later that was redeemed), the Fatherhood of God meant all the more to me.

I certainly believe that God transcends human gender, and I would not discredit the book on this basis. Still, in a New Age culture that is trying to elevate goddess-worship, portraying two of the three members of the triune God in female form for most of the book may not be entirely healthy.

Is God as tolerant and easy-going as The Shack portrays Him? If He were, I’m not sure it would have been necessary for Christ to go to the cross for us. And if the response is, “Since Christ did go to the cross God is now tolerant and easy-going,” I would suggest re-reading the New Testament where God calls us to a life of joyful yet serious holiness.

One reviewer said “Systematic theology was never this good.” This concerns me. While to some readers God will seem bigger, in certain respects God seemed more amusing and friendly, but also somewhat smaller, more manageable, less threatening—someone not to be feared. If the picture of God in The Shack is radically different from the impression people get from just reading the Bible, then that raises an obvious question.

Read Isaiah 6 and Ezekiel 1 and ask yourself if this is the “Papa” of The Shack. Chuck Colson suggested that this book fails to portray God’s person in His awesome greatness. Al Mohler, president of Southern Baptist Theological Seminary, also expressed this same concern, and pointed out what he considers “undiluted heresy” in The Shack on his April 11, 2008 radio program.

Where Is the Great God of Holiness and Transcendence?

In Tim Challies’s original review of The Shack, he says,

One of the most disturbing aspects of The Shack is the behavior of Mack when he is in the presence of God. When we read in the Bible about those who were given glimpses of God, these people were overwhelmed by His glory. In Isaiah 6 the prophet is allowed to see “the Lord sitting upon a throne, high and lifted up” (Isaiah 6:1). Isaiah reacts by crying out “Woe is me! For I am lost; for I am a man of unclean lips, and I dwell in the midst of a people of unclean lips; for my eyes have seen the King, the Lord of hosts” (Isaiah 6:5)! Isaiah declares a curse upon himself for being a man whose lips are willing to utter unclean words even in a world created by a God of such glory and perfection.

When Moses encountered God in the burning bush, he hid his face for he was afraid to look at God's glory (Exodus 3:6). In Exodus 33 Moses is given just a glimpse of God's glory, but God will show only His back saying “you cannot see my face, for man shall not see me and live” (Exodus 33:20). Examples abound. When we look to the Bible's descriptions of heaven we find that any creatures who are in the presence of God are overwhelmed and overjoyed, crying out about God’s glory day and night.

But in The Shack we find a man who stands in the very presence of God and uses foul language ("damn” (140) and “son of a bitch” (224)), who expresses anger to God (which in turns makes God cry) (92), and who snaps at God in his anger (96). This is not a man who is in the presence of One who is far superior to Him, but a man who is in the presence of a peer. This portrayal of the relationship of man to God and God to man is a far cry from the Bible's portrayal. And indeed it must be because the God of The Shack is only a vague resemblance to the God of the Bible. There is no sense of awe as we, through Mack, come into the presence of God.

Gone is the majesty of God when men stand in His holy presence and profane His name. Should God allow in His presence the very sins for which He sent His Son to die? Would a man stand before the Creator of the Universe and curse? What kind of God is the God of The Shack?

(A more recent review from Challies is available here.)

I do think that the name Papa can be appropriate, in the sense where “Abba [Daddy, Papa] Father” is used in Romans 8. However, that intimate name depicts an aspect of our loving heavenly Father that in no way negates His holiness. The paradox of God’s nature involves both transcendence and immanence. But only immanence is apparent in The Shack.

True, it could be argued that only God’s transcendence has been taught in some churches and families, and we can’t expect a book swinging the pendulum back to the middle to avoid going too far to the other extreme. Okay, but imbalance in one place doesn’t justify the opposite imbalance. It’s not just about the Father. Read the life and words of Jesus and ask if this is the Son portrayed in The Shack. Since Jesus spoke more about hell than anyone in Scripture, wouldn’t you have expected Him to say something or even hint at its reality in this story?

Miscellaneous Doctrinal Issues

Because the author and I live in the same area, I was able to invite him to discuss his book. We sat down in a coffee shop for nearly three hours in constructive dialogue. Paul Young is a good brother, winsome and likable. He’s experienced some tough times, but God has brought him through them with grace. I had met Paul before, but this time we really got to know each other. After we talked about a lot of things, I read to him most of the parts of the book that concerned me.

When we met together face-to-face, Paul graciously agreed to respond to my questions, as I had underlined many places in the book where he has God make statements that I believed are not biblically accurate.

My thought, which I told Paul, is that through his use of words, sometimes for shock value, he speaks in such a way as to imply or suggest some unbiblical teachings, and doesn't make sufficient efforts to distance himself from false doctrine.

In The Shack, God the Father says of Jesus on the cross, “Regardless of what he felt at that moment, I never left him” (96).

But Mark 15:33-34 says, “At the sixth hour darkness came over the whole land until the ninth hour. And at the ninth hour Jesus cried out in a loud voice, ‘Eloi, Eloi, lama sabachthani?’—which means, ‘My God, my God, why have you forsaken me?’”

It’s an historic doctrine of the Christian faith that Jesus didn’t just feel forsaken (as did David who spoke the words in Psalm 22) but that He actually was forsaken by the Father. David never became sin for humanity, but Jesus actually did (2 Corinthians 5:21). And in becoming sin for us, He had to be punished, and the Father had to turn away from Him, forsaking Him on the cross as the darkness descended in mid-day. This is why Isaiah 53:10 says those harrowing words, “But the LORD was pleased to crush Him [Messiah], putting Him to grief.”

On another subject, The Shack has God saying, “I don’t create institutions—never have, never will.”

But Romans 13:1-2 says, “Everyone must submit himself to the governing authorities, for there is no authority except that which God has established. The authorities that exist have been established by God. Consequently, he who rebels against the authority is rebelling against what God has instituted, and those who do so will bring judgment on themselves.”

Similarly, God created the institution of marriage and family, and the institution of the church, which is His bride.

God is portrayed in the book as saying, “Guilt will never help you find freedom in me.”

In contrast, Christ says of the Holy Spirit, “When he comes, he will convict the world of guilt in regard to sin and righteousness and judgment” (John 16:8).

Paul writes, “Godly sorrow brings repentance that leads to salvation and leaves no regret, but worldly sorrow brings death” (2 Corinthians 7:10).

Guilt alone will not bring freedom, of course, but responding in repentance to God-inspired guilt will bring us great freedom.

No Hierarchy in the Triune God?

There are several problematic statements about the trinity. For instance, Papa says:

“When we three spoke ourselves into human existence as the Son of God we became painfully human.” He goes on to say “We became flesh and blood.”

But in the historic Christian understanding of Scripture, the trinity did not become human. Only Jesus the Son became human. Scripture reveals that the Father sent the Son, but the Father did not leave Heaven and become human.

Papa says that Jesus is fully human and “has never drawn upon his nature as God to do anything.” But don’t we see repeated examples in the gospels of Jesus doing this very thing, showing His divine nature through His miracles, including raising the dead?

The Shack has God the Father say:

“Mackenzie, we have no concept of final authority among us, only unity. We are in a circle of relationship, not a chain of command or 'great chain of being' as your ancestors termed it. What you're seeing here is relationship without any overlay of power. We don't need power over the other because we are always looking out for the best. Hierarchy would make no sense among us.” He also says, “Papa is as much submitted to me as I am to Him.”

In contrast, Scripture says, “But I want you to understand that the head of every man is Christ, the head of a wife is her husband, and the head of Christ is God” (1 Corinthians 11:3).

In John 6:38 Jesus says “I have come down from heaven, not to do my own will but the will of him who sent me.”

In John 8:28 he says, “I do nothing on my own authority, but speak just as the Father taught me.”

Consider Christ in Gethsemane. Mark 14:36 says:

“Going a little farther, he fell to the ground and prayed that if possible the hour might pass from him. ‘Abba, Father,’ he said, ‘everything is possible for you. Take this cup from me. Yet not what I will, but what you will.’”

And Christ was not just subject to the Father when He walked the earth. He will be subject to Him forever:

“When all things are subjected to Him, then the Son Himself also will be subjected to the One who subjected all things to Him, so that God may be all in all” (1 Corinthians 15:28).

The book portrays all hierarchy as a result of sin, but the Bible shows there is an eternal benevolent hierarchy within the Triune God. The Shack depicts Jesus as saying, “In fact, we are submitted to you in the same way [as we are to each other].”

Where does Scripture ever say that the Father submits to the Son or the Spirit? I can’t find a single passage that says that. And, in what sense does God ever submit to us? Yes, He serves us, washes our feet, but that is not submission, which in its normal sense is a placement under the authority of another, to do their will.

Jesus came to serve, but God does not place Himself under our authority and will. That is a false doctrine that some health and wealth preachers advocate, that when we speak a word God is obligated to fulfill it. Now, I don’t believe that is Paul Young’s intention, but his statement that God submits to us is not true to Scripture.

Universalism? Are All Forgiven?

The Shack portrays God as saying that He has already reconciled the whole world. He quotes 2 Corinthians 5:19, “God was in Christ reconciling the world.” Paul Young’s position is that the world has been redeemed from God’s side, but we must embrace it from ours. Okay, in a sense that might be true, but if taken too far it sounds like everybody’s going to Heaven. Would a reconciled person go to Hell?

The fuller context of 2 Corinthians 5 says this:

All this is from God, who reconciled us to himself through Christ and gave us the ministry of reconciliation: that God was reconciling the world to himself in Christ, not counting men's sins against them. And he has committed to us the message of reconciliation. We are therefore Christ's ambassadors, as though God were making his appeal through us. We implore you on Christ's behalf: Be reconciled to God.

Notice that the apostle Paul is imploring people to be reconciled to God, which means they are not yet reconciled to God. You would not call upon a saved person to become saved, since he already is. So, yes, God was reconciling the world to himself in Christ, but in another sense this reconciliation is not and never will be experienced by the whole world. If it were, then contrary to Christ’s words in Matthew 7, the way would not be narrow and there would not be few who find it. Most or all would find it. And the road to eternal death would not be broad or even narrow—it would be nonexistent, since everyone is already reconciled to God.

In The Shack, Mack is understandably confused by the notion that the whole world is already reconciled. He asks, “The whole world—you mean those who believe in you, right?”

God replies, correcting him, “The whole world Mack.”

It would be nice if the whole world were saved, that all were going to Heaven, and that there were no hell. But according to the Bible, that’s not the case.

Papa says in The Shack: “In Jesus I have forgiven all humans for their sins against me.”

If we were already forgiven, Scripture would not say things like this:

“All the prophets testify about him that everyone who believes in him receives forgiveness of sins through his name" (Acts 10:43).

God says that not all have been forgiven or will be:

“Repent of this wickedness and pray to the Lord. Perhaps he will forgive you for having such a thought in your heart” (Acts 8:22).

“I tell you, whoever acknowledges me before men, the Son of Man will also acknowledge him before the angels of God. But he who disowns me before men will be disowned before the angels of God. And everyone who speaks a word against the Son of Man will be forgiven, but anyone who blasphemes against the Holy Spirit will not be forgiven” (Luke 12:8-10).

I asked Paul Young if he believes in the inspiration and authority of Scripture, over all personal experiences, and he said yes, absolutely. I asked him what he believed about hell. He said he’d be delighted to find it doesn’t last forever. I said I would be too, but Scripture contradicts that notion. Jesus made clear in Matthew 25:46, when He used the same word to describe the duration of punishment in hell as the duration of life in Heaven, that it does last forever: “Then they will go away to eternal punishment, but the righteous to eternal life.”

There are at least two kinds of universalism. One maintains that people can be saved apart from the Person and Work of Christ. Another claims that people can only be saved on the basis of what Christ has done, and eventually must come to recognize that, but that recognition may come after they die and are given a second chance. Then, when given that second chance, all people will choose Christ and be saved.

When I asked Paul if he was a universalist he made clear that there is no salvation without Christ—salvation is purchased only by the work of Christ. What was less clear is whether it is actually necessary to personally place one’s faith in Christ in this life, in order to be saved, and whether in fact, somehow all people will one day be saved.

Since Paul and I first met, two people who know Paul personally have said they were convinced Paul is a universalist. So I emailed Paul and asked him, “Have you written anywhere your position on hell? Or having a second chance after death to accept Christ? In the last month two different people who say they know you personally (as far as I can tell they don’t know each other) have claimed that you believe all people will be saved or at least have the opportunity to be saved after death. I wanted to go to the ‘horse’s mouth’ to ask you if they are mistaken.”

Paul graciously emailed me back saying this: “The most I have written is in my article called ‘The Beauty of Ambiguity (Mystery).’ As you know, people often think they know you better than you yourself do...oh well.”

I read the article and didn’t find a clear answer, but you may find it helpful.

James DeYoung, a professor from Western Seminary, wrote a lengthy critique of The Shack, which later became a book, Burning Down “The Shack”. He argues that Paul Young is a universalist, and that The Shack reflects this. Dr. DeYoung, who knows Paul Young personally, shares other concerns too. I asked Paul about Dr. DeYoung’s review. He felt it was inaccurate on a number of points.

When I read Paul’s book without any preconceived notions, I noticed things in The Shack that hint at universalism. For example, in the passage where “Papa,” God the Father, says—speaking of Buddhists and Muslims—that he doesn’t desire to make them “Christian.” What the author means by “Christian” is obviously critical. Paul told me that those who are Buddhists or Muslims should become Christ’s followers, yet do so in the context of their culture, not ours. But why does Papa say he doesn’t try to make them Christian? Because, Paul says, in the world’s language “Christian” is a cultural designation, that all Americans are Christian, Saudis are Muslim, etc., and that Christian is not a helpful term.

There is some truth to that, but I pointed out that Acts 11 says the disciples were first called Christians at Antioch. That wasn’t cultural; it meant to be a true follower of Christ. So since this is in the Word of God, I don’t think it’s wise to portray God as disregarding the term “Christian” to the point that He would say He doesn’t want to make people Christian. Paul said he saw the point.

Some understand Papa to be saying that He makes Muslims his children without them needing to become Christians. This is one reason why a number of readers believe the book teaches universalism. Dan Lockwood, president of Multnomah Bible College at the time, in his review of The Shack in a school publication, commended some aspects of the book, while expressing his regret that it advocates universalism.

The problem is compounded because Paul Young has God quoting a phrase coined by Buckminster Fuller, a Unitarian-Universalist who wrote a book entitled I Am a Verb. In The Shack, Papa says to Mack, “I am a verb. I am that I am. I will be who I will be. I am a verb! I am alive, dynamic, ever active, and moving. I am a verb.” It’s hard not to link this emphatic statement, put in God’s mouth, to the heretical theological persuasions of the man who coined the term.

Jesus says to Mack that he is the “best way” any human can relate to Papa. But this has a different feel from John 14:6, in which Jesus says “I am the Way, the Truth, and the Life; no one comes to the Father but by Me.” I would probably not make anything of that if I didn’t sense the tones of universalism in a number of the book’s statements.

I once saw someone who calls himself a “Christian universalist” defending his position that all will be saved. This universalist recommended a book that everybody should read: The Shack. Now, I don't believe in guilt by association. Some unorthodox people have liked some of my books. I'm just saying that since this guy was defending universalism when he recommended The Shack, he, at least, understood it to be on his side.

It would have been very easy for Paul, by changing the wording of a few sentences here and there, to shut the door on universalism. He could have had God articulate the biblical and orthodox viewpoint of historic Christianity, that salvation comes in believing in Jesus Christ and His work on the cross on our behalf, and that to not accept God’s gift of eternal life in Christ is to invite an eternity in Hell. Paul hasn’t chosen to make that clear, which he could by revising future editions of The Shack. But though he’s been aware of these concerns for a long time as far as I know he’s never made the changes he could so easily have made. While Paul was hesitant in our conversation to call himself a universalist, it seemed clear to me that he considered universalism a viable Christian belief.

Update as of February 2017: A post on Paul’s official website, written by Wade Burleson, says

Paul Young told me he is a “hopeful universalist.” He believes that our loving God sent His Son to die for every single sinner without exception. One day God will effectually reconcile every sinner to Himself. Paul uses the term “hopeful” universalism because he understands that the Scriptures speak of judgment, but Paul is “hopeful” that even in judgment, the love of God will eventually bring the sinner being judged to love for Jesus Christ. Paul Young is “hopeful” that the fire of God’s love will eventually and effectually persuade every sinner of God’s love in Christ.

Accuracy and Precision in Language

In The Shack, God tells Mack that he has never disappointed him.

Scripture tells a different story, for instance about Jesus and his response to others: “He looked around at them in anger and, deeply distressed at their stubborn hearts….” (Mark 3:5).

To believers Scripture says “And do not grieve the Holy Spirit of God, with whom you were sealed for the day of redemption” (Ephesians 4:30).

1 John 2:28 encourages believers not to do anything to make Christ ashamed of us (meaning it is possible to do so): “Now, little children, abide in Him, so that when He appears, we may have confidence and not shrink away from Him in shame at His coming.”

So why, I asked Paul, did Papa say he was never disappointed in Mack? Because, he said, to be disappointed is to have expected something that didn’t happen, but God can’t expect what doesn’t happen because he is omniscient.

I said, “Then what you really meant to have God say, was ‘I have never been surprised when you sinned.’” He said, “Yes, exactly.”

So I said, “I have to wonder, if you mean God isn't surprised by our sin, why don’t you just say that?”

And the answer may be, it’s too obvious and it’s not edgy and controversial. Well, I don’t mind edginess, but let’s be sure it’s edgy-true, not edgy-false.

In The Shack, God says “the word responsibility isn’t in the Bible.” Of course, no other English word appears in the Bible either, but he is obviously talking about “responsibility” not being in English translations. But this is inaccurate anyway, as I found “responsibility” in five major English translations, which is every one I checked except the KJV. (And you’d think God would know that, wouldn’t you?) This is the danger of putting words in God’s mouth—when you can show they’re not true it doesn’t look good.

But even apart from having God make this misstatement, what impression is left? That responsibility isn't a biblical concept. Yet isn’t it hard to find something that is more of a biblical concept than responsibility?

A hundred passages demonstrating responsibility could be cited. Here’s one:

That servant who knows his master's will and does not get ready or does not do what his master wants will be beaten with many blows. But the one who does not know and does things deserving punishment will be beaten with few blows. From everyone who has been given much, much will be demanded; and from the one who has been entrusted with much, much more will be asked. (Luke 12:47-48)

When I asked Paul why he said responsibility isn’t in the Bible, he said he meant God wasn’t in favor of responsibility in the sense of man-imposed rules and regulations and legalism. Well, okay. But do his readers understand that? Is this what the word “responsibility” means? Do we have the freedom to turn a good word into a bad one without explaining what we mean?

In the context of The Shack there is a possible explanation, because God says, “I’m omniscient—so I have no expectations.”

Well, God is omniscient, but He nonetheless has expectations of us in the normal sense of the word. For instance, look at these passages:

Now it is required that those who have been given a trust must prove faithful (1 Corinthians 4:2).

He has showed you, O man, what is good. And what does the LORD require of you? To act justly and to love mercy and to walk humbly with your God (Micah 6:8).

But I tell you that men will have to give account on the day of judgment for every careless word they have spoken (Matthew 12:36).

God’s Transcendence, Justice, Holiness, and Wrath

In theology there is a paradoxical mix of God’s attributes. There is God’s transcendence and His immanence, His Holy Otherness and His intimate Familiarity. God’s attributes are sometimes described as being of two kinds, hard and soft. Hard ones are holiness, justice, and wrath. Soft ones are grace, mercy, and love. Whether or not you like the terminology, you get the point. A full and accurate picture of God requires both be included.

The Shack is sometimes strong on the soft attributes of God. It is virtually silent on the hard attributes of God. So if you come to the book well-schooled in God’s holiness, justice, and wrath, you will benefit from the exposure to His grace, mercy and love. But if you come without a knowledge of and an appreciation for His “hard” attributes, you will end up seeing half of God, not the whole of God.

Is a half picture of the true God a false picture of God? If that’s all you have, I’d say yes. I don’t mean it’s fair to expect one book to be fifty/fifty on the hard and soft attributes of God. If I were reading a book on the holiness and justice of God and someone said “there’s not much here on His grace,” I’d say, “Of course not, it’s a book on holiness.” However, if there was virtually no mention of grace and mercy that would be problematic. Similarly, the fact that there is virtually no mention of God’s holiness, justice, and wrath in The Shack is problematic to me.

I’m not expecting complete balance. But I do think it’s fair to expect some clear affirmation of the transcendence of God. If the book is about His immanence, I can understand why 90% of it is on that. But if 10% affirmed His transcendence, it would make for a far more biblically accurate picture of God.

I asked Paul if he believes in God’s holiness and our need to fear Him? “Absolutely.” But it wasn’t the theme of this book. I told him I understood—yet took some issue with it—since people used to have a concept of God’s holiness that many of his readers will not have. Holiness and fearing God warrant at least a few sentences.

When Mack says something like “I thought you would have more wrath,” what an opportunity to briefly but clearly affirm God's holiness and wrath. Papa could say, “Mack, I am holy beyond your comprehension, and wrathful against sin to the degree that I will separate all sin from myself for eternity; that is hell.” That's just one sentence. Then he could say, “But you've heard only about my holiness and wrath, and you need to see a different side of me.” Then, great, he can go on for page after page and chapter after chapter about grace and forgiveness and acceptance, which is beautiful and right on.

Pastors who are obeying Scripture by teaching true doctrine and correcting false doctrine could then say, “The author affirms God's holiness and wrath, so I can trust that he’s not distorting or rejecting Scripture, and resorting to a New Age feel-good redefine-God-however-I-want approach.”

Often I attached what I would consider the plain or normal meanings of words Paul wrote in The Shack. But when I asked him for clarification, I discovered that he actually meant something quite different. However, in my opinion, responsibility falls on the writer to help his readers understand what he means through the words he uses. Paul originally wrote the book for his children, and perhaps they understand what he means, since they grew up in his home. But millions of readers haven’t, and many of them will believe that the words used in the book really mean what they appear to.

True, some will misunderstand no matter what. But a lot of people would be greatly helped by more careful word usage, and not be put off by or sucked into biblically incorrect thinking. Paul believes God definitely has standards and will hold us accountable if we don’t live up to them. I encouraged him to be more careful to say what he really means, and to not have God say things that are demonstrably inaccurate.

In The Shack Papa says (in the context of Mack bringing up God pouring out bowls of wrath on people), “I don’t need to punish people for sin. Sin is its own punishment, devouring from the inside. It’s not my purpose to punish it; it’s my joy to cure it” (120).

It is certainly His joy to cure it, no doubt about it. But does that mean God does not actually punish sin? Of course He does, and not exclusively through its natural consequences. Scripture speaks of God’s direct judgment via the flood, on Sodom and Gomorrah, on Dathan and the rebels. In the New Testament, He strikes down Ananias and Sapphira for their sin, and judges the sin unto death. He says that some are weak and sick in Corinth because of their abuse of the Lord's Supper, meaning He has punished them. Countless Scriptures deal with God punishing sin, but here are just a few:

“But because of your stubbornness and your unrepentant heart, you are storing up wrath against yourself for the day of God's wrath, when his righteous judgment will be revealed. God will give to each person according to what he has done” (Romans 2:5, 6).

“They called to the mountains and the rocks, ‘Fall on us and hide us from the face of him who sits on the throne and from the wrath of the Lamb! For the great day of their wrath has come, and who can stand?’” (Revelation 6:16, 17).

The Local Church

One major point of disagreement I have with Paul Young is on the importance of the local church. Without the church, there is no accountability to others, no context for confrontation and discipline among an assembly of God’s people where there is submission to those in authority, as Hebrews 10 and 13 require of us.

Before I knew anything about the author, as I read the book I kept saying to myself, “Wow, he’s had really bad church experiences.” Organized religion, by which he means churches, is portrayed unfavorably. The author's experiences had put a bad taste in his mouth concerning churches, so that though speaking in churches, at the time he said he was no longer involved in one. That helps account for the feeling of individualism I had as I read. Ironically, as I told Paul, he decries individualism in the book, but demonstrates it in his view of the church (as well as all hierarchy being wrong).

True, Paul has lots of fellowship with Christians, and has wise advisors in his life. But he chooses whom he spends time with and who his advisors will be. If he doesn’t like their counsel, he can change advisors. In contrast, when I disagree with my leaders at my church, I am called upon to submit to them, whether or not I like it. I can and do go to them to discuss it. But if they disagree, I can’t just go cross my leaders’ names off and find someone who will mirror back my opinions. (Yes, I have the option of leaving my church, but would only do this in an extreme case.)

Paul assured me that his business partners, Brad Cummings and Wayne Jacobsen, were wise and biblically based brothers in Christ, and they were his primary source of accountability. Sadly, within a few years of that conversation, Paul filed a lawsuit against these very men, claiming they had grossly underpaid his royalties. In turn, they countersued for $5 million in federal court, claiming they had co-written The Shack with Paul. Just before the case went to a jury trial, there was an out-of-court settlement, the terms of which were not divulged.

Paul’s belief is that a follower of Christ need not be part of a local church, and in many cases (including his own) is better off not being part of one. Paul thinks that if one finds fellowship, is accountable, has “elder-type” advisors he meets with regularly, and studies the Word with people, this is enough. No local church is necessary.

I told him I disagree with this, citing Hebrews 10, which says we are not to forsake the church assembly, and Hebrews 13:17, which says this:

Obey your leaders and submit to their authority. They keep watch over you as men who must give an account. Obey them so that their work will be a joy, not a burden, for that would be of no advantage to you.

We need to be in submission to church leaders and other authorities in our life; we shouldn’t think we are qualified to hold ourselves accountable, or to pick and choose our spiritual guides. That structure implies I am my own authority.

I was a pastor for fourteen years, but have not been a pastor for over twenty-five years. I’ve spent twice as much time in my adult life not being a pastor than being one, so I don’t think I’m just being defensive of pastors and churches. I’ve seen plenty of regrettable things in churches, but I’ve also seen the presence of God’s Holy Spirit in powerful ways.

I encouraged Paul to show, in his writing and speaking, the other side of churches, the side where they reach out and love and give people a home, where pastors love and graciously guide and don’t abuse power to exploit and subjugate people. He seemed to take my words seriously, and said he would consider how best to do this.

I gave him a few examples where I’ve been alarmed by readers’ misunderstandings of some of my books, then gone back and changed the words for subsequent printings. He promised to consider my suggestions for more precise wording and go over it with his advisors. (As far as I’m aware, no changes were made, but I can’t be certain of that.)

We prayed together as brothers, and hugged. I exchanged several emails with him, and we agreed to meet again.

People’s Defense of the Book

Two of our pastors led an evening discussion at our church, centered on The Shack. One expressed why he liked the book and the other presented his concerns about it. I think that was very healthy. However, some people attending got extremely upset by the criticisms, even though they were sensitively expressed. In fact, I was sitting next to a couple who were red faced and very angry when the one pastor criticized The Shack.

I tried to explain to them what the pastor was saying, and what Scripture says on the issues, but they wouldn’t listen. They loved The Shack and their minds were made up that no one should criticize it. In fact, I couldn’t help but think they were viewing this good-hearted pastor as one of those self-righteous authoritarian church leaders alluded to in The Shack. Actually, this pastor was just trying to live up to what Titus 1:9 says a church leader is to do: “He must hold firmly to the trustworthy message as it has been taught, so that he can encourage others by sound doctrine and refute those who oppose it.”

I think it’s good for pastors to discuss with their people this book or any other that is being widely read in the church. It’s important that the discussion be balanced, and not be just a “Shack Attack.” If they offer criticism, pastors should anticipate the question, “Why are my pastors opposing a book that God used to bring such joy and healing to my life?” I suggest pastors affirm the joy and healing, and say they think people would benefit even more from the book if they were careful to recognize the parts that aren’t consistent with Scripture.

I rejoice for the people who feel a greater closeness to God from reading The Shack. I only wish God’s holiness and our need to come to Him in awe, and a high regard for the local community of believers, were as apparent in the book as God’s grace and love and warmth. However, for those who need to sense more of the latter, and who can blow away the chaff and stick with the grain, I pray God will use the book to help them.

Honestly, The Shack was not life-changing for me. To me it didn’t have anything close to the power of other books, including Tozer’s Knowledge of the Holy and Packer’s Knowing God and Piper’s Desiring God and Bridges’ The Joy of Fearing God. These nonfiction books are full of Scripture, and stay true to it, and that is where they get their power. God promises in Isaiah 55:11, “My word that goes out from my mouth: It will not return to me empty, but will accomplish what I desire and achieve the purpose for which I sent it.” Notice He doesn’t promise that about our words, but His Word. If someone objects that it’s unfair to compare fiction with nonfiction, remember that The Shack actually puts words into the mouth of God. Therefore it seems reasonable to expect those words to be true to Scripture. Only when they are do we have reason to believe God will use them to accomplish His purposes.

I don’t want to discredit or oppose what God is doing through The Shack. (That’s exactly why for five years I did not make my criticisms available, except to those who specifically requested to see them.) I do believe this: if the book were revised to make it conform more closely to Scripture, God would surely be more honored and pleased with it.

There are more issues with The Shack that others have raised, and others I discussed with Paul, but I think these I’ve mentioned are some of the more important ones.

Conclusion

Someone told me The Shack contains “subtle but strong and systematic undermining of all—even healthy and godly—authority. The author does it brilliantly…” Certainly the many people who have become anti-church will feel affirmed in no longer being part of a church when they read the book Lies We Believe About God.

The fact that Eugene Peterson and a number of other Christian leaders read and loved The Shack, and speak glowingly of it without making qualifications, has been unfortunate. If he’d had editors who paid more attention to some of the unbiblical statements put in God’s mouth, the book could have been much stronger. (It still could be, if it were revised.) As for Lies We Believe About God, it would take more than strategic editing to make this book true to Scripture.

If The Shack is 90% truth and 10% error, the question is, how important is that 10%? Personally, I believe it is very important. The percentage of truth in Lies We Believe About God is, in my opinion, considerably lower yet.

God is to be worshipped and approached with reverence and awe. If you have a proper view of God and His holiness and transcendence, then The Shack might help you appreciate His intimate and tender love and grace. Unfortunately, fewer people than ever have that foundational concept of God’s holiness and the proper reverence for God. In my opinion, those who don’t will not come to a realization of God’s holiness in the book, nor will they walk away with any sense of why they should fear God in the biblical sense.

I know wonderful people who say they’ve been drawn closer to God through reading The Shack. When people feel closer to God, I wholeheartedly rejoice. But I fear some readers (not all, by any means) may feel closer to a God who is different than the God revealed in Scripture. My concern is for those who think they are coming closer to God, when they may actually be altering the biblical revelation of God into a form that is more pleasant to them because He seems less holy and fearsome. If that’s the case, then they’re not closer to God at all, just closer to a false God, an idol constructed in the image of our contemporary need for acceptance, and forged by our resistance to repentance, submission, and accountability.

We, as we are, must bow our knees to Him, as He is. And we must fully trust His Word in order to understand who He is and who we are. I write books, and have grown tremendously through reading books, so I would be the last one to say God can’t use books to enrich us greatly. But in the end, there is only One Book by which all others, mine included, must be judged.

“Now the Bereans were of more noble character than the Thessalonians, for they received the message with great eagerness and examined the Scriptures every day to see if what Paul said was true” (Acts 17:11).

Postscript, Added March 27, 2017 after the Publication of Paul Young’s Lies We Believe About God

In reading Paul Young’s book Lies We Believe About God, I was amazed to see him speak more clearly about some of his beliefs that shaped The Shack. Much of this new book demonstrates that many critics of The Shack, who were accused of overreacting, were accurate in their briefs that false doctrine accounted for some of what was in The Shack. Personally, as I read Lies We Believe About God, I marveled and grieved at some of the precious truths the author is calling falsehoods. For instance, he claims all these are lies:

- God is good. I am not.

- God is in control.

- God does not submit.

- God wants to use me.

- You need to get saved.

- Hell is separation from God.

- The Cross was God’s idea.

- Not everyone is a child of God.

- Sin separates us from God.

These are not lies. They are truths, and there is plenty of biblical support for each of them. Of course, not everything everyone says related to these truths is accurate (but that’s always true). To say these are all “lies” is unbiblical, irresponsible, and misleading.

While Paul Young remains a likable person, this doesn’t change the danger of revising God’s truth and telling people nice-sounding things on God’s behalf, when some of those explicitly contradict what He tells us in His Word.

What God said to Jeremiah about the dreams and words of so-called prophets in that day applies to us today when it comes to our choice between believing what God has said in His revealed Word, or believing the new and more appealing things that people say to replace biblical teachings:

“I have heard what the prophets say who prophesy lies in my name. They say, ‘I had a dream! I had a dream!’ How long will this continue in the hearts of these lying prophets, who prophesy the delusions of their own minds? They think the dreams they tell one another will make my people forget my name, just as their ancestors forgot my name through Baal worship.

Let the prophet who has a dream recount the dream, but let the one who has my word speak it faithfully. For what has straw to do with grain?” declares the Lord. “Is not my word like fire,” declares the Lord, “and like a hammer that breaks a rock in pieces?

“Therefore,” declares the Lord, “I am against the prophets who steal from one another words supposedly from me. Yes,” declares the Lord, “I am against the prophets who wag their own tongues and yet declare, ‘The Lord declares.’

“Indeed, I am against those who prophesy false dreams,” declares the Lord. “They tell them and lead my people astray with their reckless lies, yet I did not send or appoint them. They do not benefit these people in the least,” declares the Lord.”

Jeremiah 23:25-32