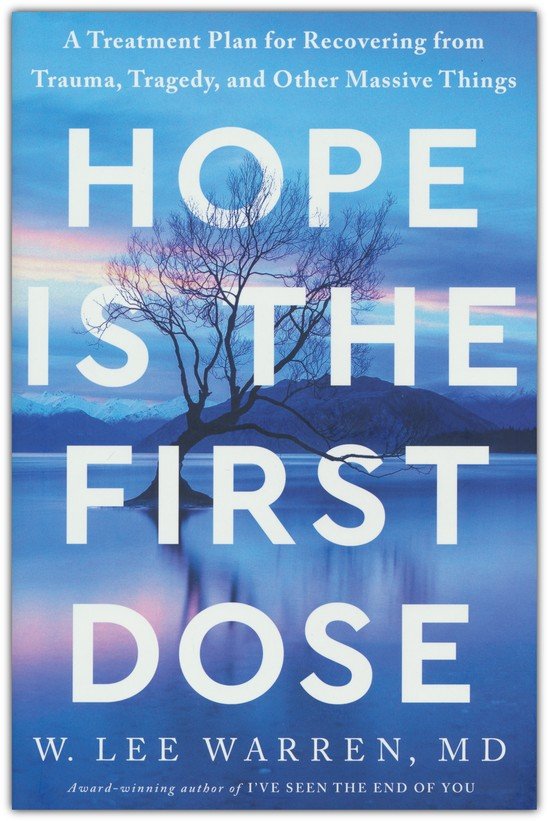

Note from Randy: Lee Warren is not a rocket scientist, but he is a brain surgeon. He is also a brother who understands both suffering and God’s grace and kindness in the deepest trials. I got to know Lee while my beloved wife Nanci was dying of cancer. We developed a quick friendship, partly because when we talked I never doubted whether he got it. I love Lee’s tender heart and warm wisdom, and both are everywhere evident in his new book Hope Is the First Dose.

Dr. Warren also has a great podcast, and I’ve had the privilege of being on it twice. The first time was to talk about happiness, and how to find delight even in the midst of difficult circumstances. The second time was to talk about the hope of Heaven, and how that hope sustains us through grief.

I hope you find this excerpt from Hope Is the First Dose helpful. In our pain and grief, may we turn to Jesus, our true source of comfort, hope, and peace. “This is my comfort in my affliction, that your promise gives me life” (Psalm 119:50).

I‘ve performed thousands of surgeries in my neurosurgery career. But probably the most difficult one was to save the life of a little boy named Mason who’d hit his head in a playground accident, just a few weeks after my own son died. The surgery went well, but I was almost overwhelmed with the guilt of saving someone else’s child, when I had been powerless to save my own. As I often do, I retreated to the hospital chapel to sort myself out after the procedure.

Ever since I was a medical student, I have found myself in hospital chapels when I’m struggling with difficult situations. Something about the quiet and the stained glass seems to center me when the hospital is too much to bear. And at East Alabama Medical Center, Pastor Jon had an uncanny ability to show up when I needed someone to talk to.

But I hadn’t been in this chapel since before Mitch died.

Over the years, whenever I was stressed, hurting, or preparing my mind for a tough case, I’d come to the chapel. Once, I’d run into a crisis of faith when I struggled to understand how to doctor someone when I couldn’t save them from their brain tumor. Pastor Jon had helped reframe my thinking, particularly about prayer. He was my sounding board as I worked through the stitching together of faith and science that led me to begin writing I’ve Seen the End of You, back when I thought I had learned about pain by studying people going through it.

But that was before I lost my boy; now I was in the depths of it myself.

It was also in this room that Pastor Jon had told me he’d lost not just one child—a little girl born with congenital heart disease—but his son as well, who had died in a car accident as a young adult.

I’d learned so much from him, had my faith strengthened and so many questions worked out during our talks. But now I felt restless and angry.

“This is the first operation you’ve performed since Mitch died, right?” he asked.

I nodded. “Yes. I wasn’t planning on coming back for a couple more weeks.”

“What a blessing you were here, though, for Mason and his family. You gave them back their son.”

I started to cry, and he put his hand on my shoulder. I said, “Yes. I’m glad about that. I just . . .”

I felt pressure rising in my chest, climbing its way up my throat, and I wanted with everything inside me to run away.

I stood and walked to the little table in the corner of the chapel where a box of Kleenex sat next to a foot-tall statue of Jesus on the cross. I wiped my eyes and my nose and noticed the ceramic nails in the ceramic Jesus’s hands and feet, the ceramic thorns in his crown. My right shoulder was on fire, my jaw ached, and my heart felt as though it was going to shatter into a million ceramic shards.

Pastor Jon shattered the silence. “You wish someone could give you your son back, too, right?”

I heard him but at the same time didn’t. I turned, walked back to the pew, and sat. “I’m sorry. What did you say?”

Pastor Jon put his hand on my shoulder. “You wish someone could give you your son back, too, right? That’s why you walked away a while ago,” he said.

I shook my head. “’Walked away’? What do you mean?”

He lowered his voice a little. It’s the first time I’ve ever seen you not stay to pray with a family.”

I looked away for a moment. “I didn’t even realize I did that. Prayer feels, I don’t know, just impossible. I’ve been involved in saving lives and rescuing people from pain and suffering so many times, but this feels like there’s no rescue, nothing that can ever make it better. Of all the things I’ve been through—war, divorce, tough cases—this is extraordinary.”

Pastor Jon looked at me for a second and his eyes narrowed. “I know. I’ve been there, remember? But I need you to know that you’re in a lot of danger right now, Lee.”

I pinched the bridge of my nose. “Danger?”

“Yes. This is the point where it’s so easy to make an idol out of your pain.”

I straightened. “What are you talking about?”

“Grief can be all-consuming. You’ve seen it before, right? Remember the lady who dragged her poor husband all over the country trying to save him from the brain tumor long after he’d lost all useful brain function? Because she couldn’t let him go? What was her name?”

I nodded. “Mrs. Andrews. Her husband couldn’t speak or move the last six months of his life, but she put him through surgeries for feeding and breathing tubes, took him to some quack in Houston who sold her a hundred thousand dollars’ worth of snake oil before he finally died.”

“That’s right,” he said. “She made keeping her husband alive the most important thing in her life. She couldn’t even see what was best for him or her family, couldn’t make room for God to comfort her because she made her circumstances determine how she felt. You told me that, remember? One of the things you discovered in your research was that people who think their circumstances determine their peace of mind, their faith, their happiness—they’re the ones who do the worst when hard times come, right?”

I waved a hand. “Yes, but what does that have to do with idolatry?”

“Everything,” he said. “Remember the Ten Commandments?”

“Of course,” I said.

“What are they?”

“You’re really giving me a test right now?”

He smiled sadly. “I just need you to remember the first two.”

“You shall have no other gods before me, and you shall not make an idol for yourself.”

“Very good! That’s it. So you and Lisa have a choice to make here. You’re on a mountain of pain and grief, reeling from losing Mitch and wondering how you can ever get over this, right?”

I looked down at my feet and then back at Pastor Jon. “Pretty much.”

“Okay, then here’s your choice: Are you going to let God help you, or are you going to walk away from him? You can let God be with you on this mountain, like he was with Moses. It’s scary. There are thunderclouds and lightning and darkness, and it’s terrifying. But he’ll be there with you, and he’ll give you the tools to make it through. And it hurts like he’s carving them on the stone tablet of your heart.

“It plays out in finding his promises in Scripture and holding on to them for dear life, in friends coming alongside you, in figuring out your marriage and your other kids in the context of one of you being permanently gone. Books will show up at just the right time, you’ll hear a pastor with just the right message, see a sunrise that seems particularly hopeful. Somehow, you will climb off that mountain carrying what you need to find your way again.”

His words were exactly true, and I knew it. It was already happening. Every day, someone called or emailed something that was exactly what we needed that day. The verse of the day on Bible Gateway would speak right to us, or one of the kids would text something that helped so much. And we were doing it for each other and the kids too. God was ministering to us, even when I felt so very far away from him. Every day, there was manna right in front of us, just enough.

Pastor Jon leaned closer and looked directly into my eyes. “But remember what Aaron was doing while Moses was on the mountain?” I thought for a moment. “He was in the valley, making the golden calf.”

He sighed. “Right. While Moses was doing the scary close-to-God stuff and getting the help he needed, Aaron and the rest of the people stayed away from the cloud and the fire and the darkness where God was, and they made themselves a god they could touch and feel.

“A lot of people do that with grief and pain. They fix their eyes and their hearts on a casket or a divorce or a diagnosis, they drink or do something else to numb the pain, and they spend their lives holding on to the hurt so tightly that it becomes the only thing they have. That’s basically idolatry. It’s making a god out of your circumstances instead of letting God help you process them. That’s a dangerous place to live, Lee.”

I’d never thought of it like that. I’d seen so many patients over the years who had never gotten over something that had happened to them, even if they had survived it. A cancer scare that turned someone’s world upside down and left them emotionally wrecked even though they were cured. A loss that embittered and enraged someone so much that their whole life was ruined.

“But there’s one more thing you need to know if you want to survive this and find your peace, your happiness, again,” he said.

I waved a hand. “What?”

“Losing a child is extraordinary. But, my friend, it’s also really ordinary.”

I started crying again. “How can you say that? I mean, you’ve lost two kids, which I can’t even imagine, so you know it’s not something you’re supposed to feel, and it’s certainly not an ordinary part of life.”

“Not what I meant,” he said. “Take a few deep breaths and just think about what you know from working in this building. I guarantee you that even today, someone is dying or has died. Someone is having a heart attack or holding their wife’s hand as she slips away. Zoom out to the cities around us and the amount of suffering happening in this very moment is staggering.”

“You’re not making me feel any better. I hope this isn’t your Sunday

sermon,” I said.

He huffed. “No. I’m making the point that extreme, extraordinary suffering and pain is an ordinary, normal, constant part of life. And that’s why you can find a way to make it through.”

“That doesn’t make any sense,” I said quietly.

He put his hand on my knee. “If it really were happening only to you, then it would be extraordinary, and it would be reasonable for you to feel hopeless or singled out by God or abandoned. But the extraordinarily ordinary pain of life is mixed in with all the extraordinarily ordinary amazing things too—while we’re speaking, people are being born, falling in love, achieving a long-held goal, or being baptized. Someone is holding hands or seeing a rainbow for the first time. Yes, life is really hard, but it’s also really good. All at the same time. And when you’re submerged in pain, it can be so deep and so dark that you can forget all that light is out there. But it still is.”

He put his hand on my knee. “If it really were happening only to you, then it would be extraordinary, and it would be reasonable for you to feel hopeless or singled out by God or abandoned. But the extraordinarily ordinary pain of life is mixed in with all the extraordinarily ordinary amazing things too—while we’re speaking, people are being born, falling in love, achieving a long-held goal, or being baptized. Someone is holding hands or seeing a rainbow for the first time. Yes, life is really hard, but it’s also really good. All at the same time. And when you’re submerged in pain, it can be so deep and so dark that you can forget all that light is out there. But it still is.”

Adapted from Hope Is the First Dose by W. Lee Warren, M.D. Copyright © 2023 by W. Lee Warren, M.D. Published by WaterBrook, an imprint of Penguin Random House. Used with permission.

Photo by RDNE Stock project