Mother Teresa devoted her life to helping the poorest of the poor. After observing her arduous work among the filth, disease, and suffering of Calcutta, a television commentator told her, “I wouldn’t do what you’re doing for all the money in the world.” She replied, “Neither would I.”

What we wouldn’t do for all the money in the world, we are called to do out of obedience to Christ, compassion for others, and anticipation of eternal reward.

I am always amazed when I read about acts of philanthropy to Planned Parenthood, the world’s largest abortion provider. It’s alarming how easily giving can be wasteful, or even harmful. Bernard Marcus, founder of Home Depot, gave $200 million for an aquarium in Atlanta. I’m all for aquariums, but when I see a world full of lost and hungry people, I wonder, Where are the huge gifts to Christian ministries that are devoted to reaching the lost and helping the needy in the name of Christ?”

Claude Rosenberg Jr. devoted years to researching America’s giving habits and potential and put his findings into a book titled Wealthy and Wise: How You and America Can Get the Most out of Your Giving. According to Rosenberg, most of us give away less than ten percent of what we could actually afford to give, even without making significant lifestyle changes. Does that sound incredible? If you look at it closely, you’ll see that it’s true. Rosenberg argues that Americans giving away 2 percent of their income could give away 20 percent, provided they simply made wiser choices with what they spend. He calculates that Americans could donate at least $100 billion more per year than we already do—and with a minimum of sacrifice or risk. This is without even going as far as the sacrificial giving we see in Scripture, and without calculating in the way God provides generously for givers.

According to Rosenberg, if we had a better grasp of what we actually own, most of us could double, triple, or quadruple the amount we now give.[1]

Why is this money tied up, inaccessible to God to use for his purposes? Partly it may stem from our failure to come to grips with the needs of the poor and the lost, as well as our neglect of strategic opportunities to make an eternal difference through our giving.

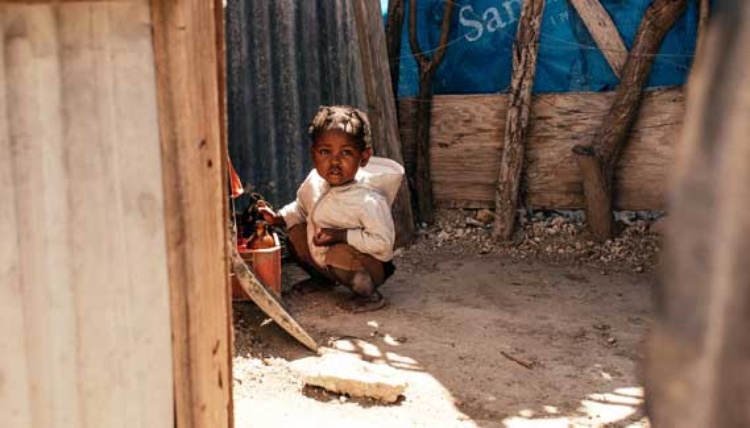

Giving to the Poor

Who Is Responsible for the Poor?

In his essay on self-reliance, Ralph Waldo Emerson writes, “Do not tell me, as a good man did today, of my obligation to put all poor men in good situations. Are they my poor?”[2] Emerson’s attitude reflects our national spirit of independence. Few of us wish harm to the poor. We just don’t want to be held responsible for them. But Emerson’s question is a valid one. Are the poor my poor? Am I responsible for their plight? More than one evangelical writer would have us believe that because we ourselves are not poor, because we have money and possessions others don’t, we are at fault for their poverty.

This perspective is a “zero sum” philosophy, the belief that wealth cannot be created but only distributed, and that for every winner there must be a corresponding loser. For example, if there are eight people at a party and a pie is cut in eight pieces, and I take two or three pieces for myself, then I’ve taken what belongs to the others. They have less because I have more.

Those holding this position apply the pie analogy to the world. There’s only so much wealth in the world, they say, and everyone’s entitled to his share. If I have more than someone else, essentially I’ve stolen from him. Karl Marx taught this concept, dividing all men into “the oppressors and the oppressed.” Those who have much are oppressors; those who don’t are oppressed.

However, unlike a finite pie that cannot be made bigger, wealth is not limited—it can be produced and enlarged. Scripture tells us, “Remember the Lord your God, for it is he who gives you the ability to produce wealth” (Deuteronomy 8:18). Wealth is being produced every day as a result of ingenuity and hard work. One person’s prosperity can take place at the expense of another, but it need not.

Is Capitalism to Blame for Poverty?

Some would claim that although we may not directly exploit the poor, we’re voluntarily part of an economic system that exploits them. Therefore, we’re culpable. In this view, capitalism is the supposed enemy of the poor.

Every discussion of the plight of the poor involves economics, so I need to address the subject at least briefly. Interested readers may turn to a number of fine books that explore the issues in depth.[3]

Capitalism is a free-market economic system that operates without exterior control. “Control” is left to what economist Adam Smith called “the invisible hand.” According to this theory, the marketplace naturally orders itself around the needs and wants of the population. The principle of supply and demand determines what sells at what price. The greater the competition, the more goods there are to choose from and the more reasonable prices will be.

It’s difficult to understand how one particular system (capitalism) can be blamed for a problem (poverty) that has existed in every country with every economic structure in human history. A capitalistic society can certainly foster greed and allow the poor to be exploited, but it can also give opportunity to the poor to do what many have done in free-market economies—work themselves out of poverty.

Capitalism results at times in exploitation, because no system can eliminate sin. But capitalism is not built on exploitation, it’s built on common interest. In a truly free market, all parties will ultimately get what they want. For example, when you bought this book, presumably you were satisfied with the transaction—you profited from the exchange of currency for ideas and principles. Who else came out ahead on the transaction? One would hope the bookseller, the publisher, and the author, as well as loggers, the paper company, the printer, truckers, and others who took part in the process. When you buy milk, who profits? You do—you get the milk you wanted. But others profit as well, including your grocer and the dairy farmer. All parties involved can profit in the buying and selling of goods. One’s profit is not at the expense of another.

The major alternative to capitalism is socialism. Some outspoken Christians still suggest it’s a better alternative. Socialism is an economic system controlled by the state. It supposedly spreads out the good to all, preventing the formation of a rich, land-grabbing elite that would oppress the poor. In socialism, economic power is centralized in the government so that no individual can become rich at the expense of others. Unfortunately, somebody has to run this system. And because power tends to corrupt, these caretakers of the system inevitably become the rich and oppressive elite. Under capitalism, a large number of the rich get richer—but so do some of the poor. Under socialism, a small number of the rich get richer, but the poor stay poor.

Those who laud socialism ignore the fact that historically the poor usually fare better in capitalist economies. They also fail to recognize that when the profit incentive is removed from labor, someone must find another way to motivate people to work. There’s only one other way that works—and that’s coercion. The capitalist says, “You scratch my back and I’ll scratch yours.” The socialist says, in effect, “You scratch my back or I’ll break yours.”

Can capitalism involve exploiting the poor? Of course. Does socialism lead to the oppression of the poor? Inevitably. The point isn’t that capitalism is a perfect system, but that the alternatives are worse. It isn’t a systemic problem, it’s a sin problem. Any economic system will work where there’s no sin. None will work ideally when there is sin, but some will work better than others.

Our Responsibility to Help the Poor

Neither God’s Word nor an accurate understanding of economics supports the notion that the prosperous are automatically responsible for making others poor. As we’re about to see, what Scripture does say is that we are responsible to help the poor. I may not be responsible for the existence of world hunger. But I am responsible to do what I can to relieve it.

So, back to Emerson’s question, “Are they my poor?” If by this he means, “Have I made them poor?” in most cases the answer is no. But if he means, “Am I responsible to help the poor?” then the answer is yes, they are indeed my poor. Of course, many have exploited the poor and need to face up to it. They should adopt the posture of Zacchaeus, who determined to pay back fourfold those whom he had cheated (Luke 19:8).

We’re not to feel guilty that God has entrusted an abundance to us. But we are to feel responsible to compassionately and wisely use that abundance to help the less fortunate. Consider the Good Samaritan (Luke 10:30-37). In contrast to the two religious leaders who passed by the poor man who had been stripped and beaten by robbers, when the Samaritan found him, he took pity on him and stopped to help. His reaction wasn’t to feel guilt and remorse. He hadn’t brutalized the man. But he took responsibility to care for him.

At great inconvenience to himself, he treated and bandaged the man’s wounds, then “put the man on his own donkey, took him to an inn and took care of him” (Luke 10:34). The next day, he paid the innkeeper to watch over the man until he could come back and resume care for him himself. Although the Samaritan wasn’t in any way responsible for hurting the man, he nevertheless took responsibility to help him however he could. “Go and do likewise,” Jesus says (Luke 10:37). Every man is our neighbor, and we are to show mercy and care for him in his need.

The Roman emperor Julian had an interesting complaint about Christians: “The impious Galileans support not only their own poor but ours as well; everyone can see that our people lack aid from us.”[4] The theologian Tertullian says, “It is our care of the helpless, our practice of loving kindness that brands us in the eyes of many of our opponents. ‘Only look,’ they say, ‘look how they love one another!’”[5]

During the time of the plague, Christians were known for coming into the cities to help the dying, rather than fleeing from the cities to save their lives. Dionysius describes this phenomenon:

Most of our brother Christians showed unbounded love and loyalty; never sparing themselves and thinking only of one another. Heedless of the danger, they took charge of the sick, attending to their every need and ministering to them in Christ, and with them departed this life serenely happy; for they were infected by others with the disease, drawing on themselves the sickness of their neighbors and cheerfully accepting their pains. Many, in nursing and curing others, transferred their death to themselves and died in their stead.[6]

Helping the poor has always set Christians apart, showing the world that we operate on a radically different value system. John Wesley says, “Put yourself in the place of every poor man and deal with him as you would God deal with you.” Wesley demonstrated this attitude in his own lifestyle choices:

In 1776, the English tax commissioners inspected his return and wrote back, “[We] cannot doubt but you have plate for which you have hitherto neglected to make entry.” They assumed that a man of his prominence certainly had silver dinnerware in his house, and they wanted him to pay the proper tax on it. Wesley wrote back, “I have two silver spoons at Londonand two at Bristol. This is all the plate I have at present, and I shall not buy any more while so many round me want bread.”[7]

What the Scriptures Say about Caring for the Poor

Caring for the poor is a central theme throughout Scripture. The Mosaic Law made many provisions for the poor, including the following:

When you reap the harvest of your land, do not reap to the very edges of your field or gather the gleanings of your harvest. Do not go over your vineyard a second time or pick up the grapes that have fallen. Leave them for the poor and the alien. I am the Lord your God (Leviticus 19:9-10).

Give generously to [the poor] and do so without a grudging heart; then because of this the Lord your God will bless you in all your work and in everything you put your hand to. There will always be poor people in the land. Therefore I command you to be openhanded toward your brothers and toward the poor and needy in your land (Deuteronomy 15:10-11).

Proverbs promises reward for helping the poor:

He who is kind to the poor lends to the Lord, and he will reward him for what he has done (Proverbs 19:17).

A generous man will himself be blessed, for he shares his food with the poor. (Proverbs 22:9)

He who gives to the poor will lack nothing, but he who closes his eyes to them receives many curses (Proverbs 28:27).

The Old Testament prophets boldly proclaim God’s commands to care for the poor:

I want you to share your food with the hungry and to welcome poor wanderers into your homes. Give clothes to those who need them, and do not hide from relatives who need your help. (Isaiah 58:7, NLT)

Feed the hungry and help those in trouble. Then your light will shine out from the darkness, and the darkness around you will be as bright as day. The Lord will guide you continually, watering your life when you are dry and keeping you healthy, too. You will be like a well-watered garden, like an ever-flowing spring (Isaiah 58:10-11, NLT).

Jesus came to preach the good news to the poor, the captives, the blind, and the oppressed (Luke 4:18-19). Of course, the gospel is for the rich and the sighted as well. It’s just that the poor and handicapped understand bondage enough to appreciate deliverance. They’re quicker to recognize their spiritual need, because it’s not buried under layers of prosperity. Though he himself had little, Jesus made a regular practice of giving to the poor (John 13:29). He repeatedly commands care for the poor, promising eternal reward:

Then Jesus said to his host, “When you give a luncheon or dinner, do not invite your friends, your brothers or relatives, or your rich neighbors; if you do, they may invite you back and so you will be repaid. But when you give a banquet, invite the poor, the crippled, the lame, the blind, and you will be blessed. Although they cannot repay you, you will be repaid at the resurrection of the righteous” (Luke 14:12-14).

Special offerings to help the poor were commonplace in the early Church:

During this time, some prophets traveled from Jerusalem to Antioch. One of them named Agabus stood up in one of the meetings to predict by the Spirit that a great famine was coming upon the entire Roman world. (This was fulfilled during the reign of Claudius.) So the believers inAntiochdecided to send relief to the brothers and sisters inJudea, everyone giving as much as they could. This they did, entrusting their gifts to Barnabas and Saul to take to the elders of the church in Jerusalem (Acts 11:27-30, NLT).

Tabitha “was always doing good and helping the poor” (Acts 9:36). Luke says of Cornelius the centurion, “He and all his family were devout and God-fearing; he gave generously to those in need and prayed to God regularly.” An angel appears in a vision and tells him, “Your prayers and gifts to the poor have come up as a memorial offering before God” (Acts 10:2-4).

Church leaders emphasize giving to the poor: “All they asked was that we should continue to remember the poor, the very thing I was eager to do” (Galatians 2:10). “Religion that God our Father accepts as pure and faultless is this: to look after orphans and widows in their distress and to keep oneself from being polluted by the world” (James 1:27). James also writes:

What good is it, my brothers, if a man claims to have faith but has no deeds? Can such faith save him? Suppose a brother or sister is without clothes and daily food. If one of you says to him, “Go, I wish you well; keep warm and well fed,” but does nothing about his physical needs, what good is it? (James 2:14-16)

The apostle John writes:

This is how we know what love is: Jesus Christ laid down his life for us. And we ought to lay down our lives for our brothers. If anyone has material possessions and sees his brother in need but has no pity on him, how can the love of God be in him? Dear children, let us not love with words or tongue but with actions and in truth. This then is how we know that we belong to the truth, and how we set our hearts at rest in his presence (1 John 3:16-19).

Caring for the poor and helpless is so basic to the Christian faith that those who don’t do it aren’t considered true Christians. Christ says if we feed the hungry, give drink to the thirsty, invite in the stranger, give clothes to the needy, care for the sick, and visit the persecuted, we are doing those things to him: “Come, you who are blessed by my Father, take your inheritance, the kingdom prepared for you since the creation of the world. For I was hungry and you gave me something to eat” (Matthew 25:34-35). Likewise, if we don’t do these things, then we’re turning our backs on Christ himself. To those who didn’t help the poor and needy, Christ says, “Depart from me, you who are cursed, into the eternal fire prepared for the devil and his angels. For I was hungry and you gave me nothing to eat” (Matthew 25:41-42).

In the full context of Matthew 24–25, those we are to help in their need seem mainly to be Christians, Christ’s “brothers,” who are in need as a result of persecution for their faith. Our first priority is to care for the needs of those “of the household of faith” (Galatians 6:10, NASB). Although the passage’s general principle can be applied to all the world’s poor, we should especially seek to find ways to help suffering Christians and especially to our persecuted brothers and sisters throughout the world in places such as Sudan, China, Indonesia, and the Middle East.

When Saul was persecuting Christians, Jesus appears to him and asks, “Why are you persecuting Me?” (Acts 9:4, NKJV). This shows how personally Jesus takes the suffering of his people. To persecute them is to persecute him. To help them is to help him.

We must ask, “If Christ were on the other side of the street, or the city, or the other side of the world, and he was hungry, thirsty, and helpless, or imprisoned for his faith, would we help him?” Any professing Christian would have to say yes. But we mustn’t forget what Christ himself says in Matthew 25: He is in our neighborhood, community, city, country, and across the world, in the form of poor and needy people—and especially in those who are persecuted for their faith.

The rich man who passed by poor Lazarus is condemned not for a specific act of exploitation but for his lack of concern and assistance for a man in need (Luke 16:19-31). The passage suggests that the rich man should either have brought Lazarus to his table or joined him at the gate. Ignoring the poor is not an option for the godly. Likewise, in the account of the final judgment, the sin held against the “goats” is not that they did something wrong to those in need, but that they failed to do anything right for them (Matthew 25:31-46). Theirs is not a sin of commission, but of omission. Yet it’s a sin of grave eternal consequence.

We cannot wash our hands of responsibility to the poor by saying, “I’m not doing anything to hurt them.” We must actively be doing something to help them.

What Can We Really Do?

“But I’m just one person. And we’re just a small church. How can we eliminate poverty?” The answer is, you can’t. Jesus said the poor would always be with us (Mark 14:7). Then, should we give up? Of course not. I saw a relief organization poster that asked the question, “How can you help a billion hungry people?” The answer it gave was right on target: “One at a time.” Just because I can’t take care of all the world’s poor doesn’t mean I can’t begin by helping one, then two, then five, ten, and so on. The logic that says, “I can’t do everything, so I won’t do anything” is from the pit of hell.

I must help the poor who are near, but also those who are far away. In fact, most of the truly poor, hungry, and persecuted people live in another part of the world. At this point, we usually hear another worn-out excuse: “Well, there’s no sense giving my money to hunger relief organizations, because the people who need the food never get it anyway.” This assertion is simply false. Yes, distribution is sometimes a major challenge, and some organizations are more efficient than others. And yes, corrupt officials or soldiers may confiscate some supplies. Nevertheless, a great deal of food does get to the hungry people. Our responsibility is to choose the best organizations we can find, give our money, pray, and trust God and our fellow servants in ministry that most of the food and supplies will get to the needy.

We should take some of our favorite excuses for not feeding the hungry and imagine stating them at the judgment seat of Christ. In light of his uncompromising command to feed the hungry, how many of our excuses will he accept?

“But feeding the hungry is just a short-term measure. They’ll be starving again unless they are taught how to feed themselves.” Many development organizations are dedicated to finding and implementing long-term solutions by teaching nationals the kinds of skills and getting them the kinds of equipment that can help them grow and harvest plenty of their own food. Are you and I giving our money, time, or prayers to help these groups accomplish their goals?

The poor need not only our provisions, but also social justice. The law says that no one should take advantage of a widow or an orphan, or God will surely punish the tyrant (Exodus 22:22-23). Likewise, aliens are not to be oppressed in any way (Exodus 23:9). God says, “Do not show favoritism to a poor man in his lawsuit,” then three verses later adds, “Do not deny justice to your poor people in their lawsuits” (Exodus 23:3, 6).

The prophets were particularly concerned about the exploitation of the poor (Amos 2:6-7;5:11-12; 8:4-6). James warns the church against courting and favoring the rich over the poor (James 2:1-13). Concern for the poor was built right into the land laws (Exodus 23:10). “I know that the Lord secures justice for the poor and upholds the cause of the needy” (Psalm 140:12).

Every church and Christian must ask, “What are we doing to feed the hungry and help the poor? What are we doing to secure justice for the poor? What are we doing to uphold the cause of the needy?” Sentiment is not enough. Why not determine a salary to live on, then give back to God every dime he entrusts to us beyond that, so every day we work and earn income is a day that will help the poor and reach the lost.

Are We Helping or Subsidizing the Poor?

The worst thing we can do to the poor is ignore them. The next worst thing is to subsidize them—that is, to help them only enough to keep them alive, but not enough to assist them in developing the means by which they might move out of poverty. The poor are frequently lumped together into one group, as if they’re all the same. They aren’t.

The all-inclusive term “the poor” is used repeatedly by some evangelicals. We’re told we must help “the poor” by doing this and that, as if it did not matter why they are poor. Yet neither Scripture nor experience indicate that all poor people are poor for the same reasons. Consequently, they cannot be truly helped by the same means.

A person may be poor for any one or a combination of the following ten reasons: insufficient natural resources; adverse climate; lack of knowledge or skill; lack of needed technology; catastrophes, such as earthquakes or floods; exploitation and oppression; personal laziness; wasteful self-indulgence; religion or worldview; and personal choices by some to identify with and serve the poor. For instance, the Hindu concept of Karma does not encourage people to initiate improving their circumstances, and their reverence for certain animals allows people to starve while one of their major God-given food sources (cattle) consumes another (grain).

So when we say, “This is what we should do to help the poor,” it’s like saying, “This is what we should do to cure sickness.” To be effective, cures must be sought and applied for specific diseases, such as cancer, heart disease, diabetes, colitis, or asthma, not for “sickness” in general. It’s as ludicrous to use one formula to “help the poor” as it is to give all sick people the same treatment for every disease and expect it to heal them.

If people are poor because their homes and businesses have been wiped out in a flood, the solution may be to give them the money, materials, and assistance to rebuild their homes and reestablish their businesses. If they’re poor because of insufficient natural resources or adverse climate, we can share the knowledge, skills, and technology necessary to help them make the best of their situation. If this is impossible, we might help them relocate.

If people are poor due to oppression or injustice in our nation, then we can do what we can to remove or mitigate the oppression. For instance, we can petition and lobby for legal, social, and economic reforms. If the needy are in another country, we may be able to apply the pressure of international opinion to bring about change. And, of course, we can pray.

If people are poor due to their religion or worldview, the problem is especially thorny. Certainly we can try to convince them to change their religion and worldview. Sharing the gospel is basic to that. Sadly, we must realize that without a fundamental religious or philosophical change, all the short-term aid we can give will never help solve the long-term problem. This doesn’t mean we should withhold aid—just that we must realize its limitations.

A person may also be poor because of self-indulgence. “He who loves pleasure will become poor” (Proverbs 21:17). Someone may make a decent income but waste it on drugs, alcohol, cigarettes, expensive convenience foods, costly recreation, or gambling (including lotteries). Some people manage to meet their family’s needs on very low incomes. Others make several times as much money, but are always “poor,” always in a financial crisis. This isn’t because their means are too little, but because they’re living irresponsibly.

We once called a government agency to get the names of some needy families. Then we drove to their homes with sacks of food—only to find people living in better conditions than some who had contributed the food. I’ve seen people who perpetually have no money to buy groceries for their family but who own nice cars and expensive electronic equipment. The government may consider this poverty, but it certainly is not. Such a person needs only to liquidate his assets to feed his family, then learn to live within his means and not squander his income. Christians shouldn’t subsidize the irresponsible but supplement the responsible.

Finally, a person may be poor due to laziness. God’s Word explicitly says that the result of laziness will be poverty (Proverbs 24:30-34). “Lazy hands make a man poor, but diligent hands bring wealth” (Proverbs 10:4). “A sluggard does not plow in season; so at harvest time he looks but finds nothing’ (Proverbs 20:4). “The fool folds his hands and ruins himself” (Ecclesiastes 4:5). Ultimately, the lazy man is poor by choice.

We shouldn’t rescue lazy people from their poverty. Every act of provision removes their incentive to be responsible for themselves and makes them more dependent on others. Paul commands the Thessalonian church to stop taking care of the lazy and reminds them of the rule he issued when present with them: “If a man will not work, he shall not eat” (2 Thessalonians3:10). In other words, it’s a sin to feed the lazy. The point is not to let people starve; the point is that people who are faced with starvation will be motivated to work and support themselves as God intended. As it says in Proverbs 16:26, “The laborer’s appetite works for him; his hunger drives him on.”

Lazy and self-indulgent people do not need financial support; they need incentives to no longer be lazy and self-indulgent. “Laziness brings on deep sleep, and the shiftless man goes hungry” (Proverbs 19:15). It isn’t our job to invalidate this principle of God’s Word. It isn’t our place to make exceptions to God’s law of the harvest that says, “A man reaps what he sows” (Galatians 6:7). Any system that feeds the lazy is a corrupt system. It does them and the rest of society a grave disservice and opposes the God-ordained structure of life.

Of course, someone can be unemployed without being lazy. We need to help the unemployed, but all the while we need to help them find work. When employment isn’t to be found, we need to provide it however we can. From time to time, only as a short-term measure, our church has helped the unemployed by giving them work on our grounds. It’s important for their self-respect and motivation to associate income with work.

If money steadily comes in to the able-bodied person who isn’t working, then money becomes disassociated from work. Such people come to believe that society or the Church owes them provision—which further encourages laziness and the destruction of self and family. A nation, social service organization, church, or individual that subsidizes the lazy spawns laziness. Rather than eliminating poverty, they perpetuate it.

The question is not simply, “What shall we do for the poor?” but “Which poor?” The truly poor must be helped. But they must be helped thoughtfully and carefully, according to the fundamental reasons for their poverty and according to their long-range best interests.

Distributing Funds to the Poor

Indiscriminate distributions to the poor can be catastrophic. Often the “professionally poor” receive goods while the true poor—those who want to work but can’t, or those who work but can’t make enough money to provide for their own needs—are hesitant to take handouts. I’ve seen a man choose not to work for a year and receive unemployment benefits that are twice as much as another man earns for a forty-hour workweek. Worse yet, I’ve seen the same man grow accustomed over that one-year period to not having to work to live. That was more than twenty years ago, and he hasn’t had a job since. He still lives off the misguided “help” of others. Meanwhile he’s lost his self-respect and his family.

There’s much to learn from the Old Testament practice of gleaning. The corners of the fields were left uncut so the poor could have food. But the grain wasn’t cut, bundled, processed, ground, bagged, transported, and delivered to the poor. Provided they were able, the poor did the work themselves—and thereby were neither robbed of their dignity nor made irresponsible by a system requiring no work. The special tithe taken at the end of every third year went to the poor, including the Levite, travelers, the fatherless, and the widows (Deuteronomy 14:28-29). It did not include able-bodied adults who simply preferred not to work.

Churches should help the needy. But “helping” means more than just giving them money or a sack of food. It requires personal attention—our time, skills, and interest. A widow doesn’t just need a check; she needs someone to take her shopping, sit with her, pray with her. She may need someone to mow her lawn, fix her fence, drive her to church. She needs not only material support but also personal support. (And she needs the latter even if she has plenty of money.)

Many people don’t need more money, but they need help in handling the money they have. Good financial counseling, including how to make a reasonable budget and stick to it, is a more valuable gift than five hundred dollars to bail someone out of a situation he should never have gotten into in the first place. Direction in how to find and keep a job is far more helpful than putting groceries on a shelf while someone sits home and watches television all day. When a middle-aged man is laid off his job, he not only needs to find a new one, but he may need support to avoid the paralytic depression that often accompanies such situations.

Churches need to develop a screening process that isn’t impersonal or dehumanizing but that accurately determines whether a person is in need, and if so, why. Paul says to care for “those widows who are really in need” (1 Timothy 5:3) and goes on to say that not every widow qualifies for church support. For instance, the church is not to take over responsibilities that belong to family members:

Give proper recognition to those widows who are really in need. But if a widow has children or grandchildren, these should learn first of all to put their religion into practice by caring for their own family and so repaying their parents and grandparents, for this is pleasing to God. The widow who is really in need and left all alone puts her hope in God and continues night and day to pray and to ask God for help (1 Timothy 5:3-5).

In light of this principle, our church has approached relatives to encourage them to meet the material needs of a family member they may be neglecting. It’s the church’s role to help and encourage the family—not to take over its responsibilities.

To distribute funds to the needy, a church must have accurate information and ongoing accountability to determine who’s needy and why, and what exactly they really need. Otherwise, we can be guilty of the very same thing our government does—trying to solve every problem by indiscriminately throwing money at it. In doing so, we often decrease incentives and increase dependence and hostility. Attempting to meet needs by giving money sometimes has the same effect as trying to put out a fire by throwing gasoline on it.

The Didache, written in the second century as a guidebook to Christian converts, says, “Let thine alms sweat in thy hands, until thou knowest to whom thou shouldst give.” When in doubt, we should err on the side of helping the poor, even though we may have to swallow our pride, and sometimes others will take advantage of us. Martin Luther was so generous he was sometimes taken advantage of. In 1541, a transient woman, allegedly a runaway nun, came to their home. Martin and Katherine fed and housed her, only to discover she had lied and stolen. Yet Luther believed no one would become poor by practicing charity. “God divided the hand into fingers so that money would slip through,” he said. [8]

Facing Up to the Poor

When asked, “What’s the secret to happiness?” Tennessee Williams responded, “Insensitivity.” Many follow this advice. We become calloused to the plight of the poor. We pretend their condition isn’t so bad, that they’re all irresponsible, that there’s really nothing we can do to help them. Or we rationalize that we’re already helping enough through paying taxes and occasionally giving to a charitable cause.

Jacques Ellul was right: “Each of us must face up to the poor.” [9] We must do so now or later, when we stand before the Judge. “If a man shuts his ears to the cry of the poor, he too will cry out and not be answered” (Proverbs21:13). God says that his willingness to answer our prayers is directly affected by whether we’re giving ourselves to help the hungry, needy, and oppressed (Isaiah 58:6-10). Do you want to improve your prayer life? Give to the poor.

It’s easy to verbalize concern for the poor but hard to implement it. For some it’s a question of getting up the nerve to walk down the block and get to know the poor. For others it’s a matter of having to drive twenty miles to find a poor person, and even then not knowing exactly where to look. That’s why it’s so easy in an affluent community to pretend the poor don’t exist.

I must ask myself, Where are the poor in my budget? Our family gives regularly to relief ministries that bring material help and the gospel to the needy throughout the world. But this isn’t enough. What current efforts am I making to find a materially needy person and help him or her? I cannot relate meaningfully to the poor when I’m isolated from the poor. Perhaps I must take regular trips away from the cozy suburbs where I live. Perhaps I need also to travel overseas, not as a tourist, but to meet needs.

Years ago, some of our church families brought warm clothes, space heaters, and supplies to help local Hispanic migrant workers through the cold winter. This led to the opening of homes and our church building to develop ongoing relationships. Some studied Spanish to further bridge the gap, deepen friendships, and share the gospel.

Whole churches have become involved in projects of helping the poor. Our church high school group has taken trips to Mexico to meet and minister to the poor. They’ve put on evangelistic Bible clubs for inner-city children. That’s a beginning. Many churches can go to the inner city, the jails, the hospitals, and rest homes—wherever there’s a need.

We need to examine our motives. It’s becoming trendy for the middle and upper classes to help the poor. It makes us feel good, soothes our consciences to make a few token gestures to the poor, then return to our lives of materialism. The challenge is not to pat ourselves on the back for giving away a sack of groceries at Christmas. It’s to integrate caring for the poor into our lifestyles.

Some seem to think that giving to a good cause is all that matters, and doing so is itself a sign of good motives. But Paul says, “If I give all I possess to the poor . . . but have not love, I gain nothing” (1 Corinthians 13:3).

We must not just open our pocketbooks but also our homes (Romans 12:13). It’s easy to be hospitable to “our own kind.” But what about the poor and the needy? I say these things not as an expert in ministering to the poor. I’m just a beginner. I have very far to go. But if I’m to be a disciple of Jesus Christ, then go I must.

May God one day say of us what he said of King Josiah: “He defended the cause of the poor and needy, and so all went well. Is that not what it means to know me?” (Jeremiah 22:16)

Excerpted from Randy Alcorn’s book Money, Possessions, and Eternity.

[1] Claude Rosenberg Jr., Wealthy and Wise: How You and America Can Get the Most out of Your Giving (Boston: Little, Brown, and Company, 1994), 13–17.

[2] Ralph Waldo Emerson, “Self-Reliance,” in Essays and Lectures (New York: Library of America, 1983), 261–62.

[3] See Ronald Nash, Poverty and Wealth (Westchester, IL: Crossway, 1986); John Jefferson Davis, Your Wealth in God’s World (Phillipsburg, NJ: Presbyterian and Reformed Publishing, 1984); Brian Griffith, The Creation of Wealth (Downers Grove, IL: InterVarsity Press, 1984); and R. C. Sproul Jr., Money Matters (Wheaton, IL: Tyndale House, 1985).

[4] Os Guinness, Doing Well and Doing Good: Money, Giving, and Caring in a Free Society (Colorado Springs, CO: NavPress, 2001), 128.

[5] Ibid.

[6] Ibid.

[7] John Wesley, quoted in Charles Edward White, “Four Lessons on Money from One of the World’s Richest Preachers” Christian History 19 (summer 1988): 24.

[8] Mike Galli, “Did You Know?” Christian History Issue 39 (Vol. XII, No. 3).

[9] Jacques Ellul, Money and Power (Downers Grove, IL: InterVarsity Press, 1984), 151–52.